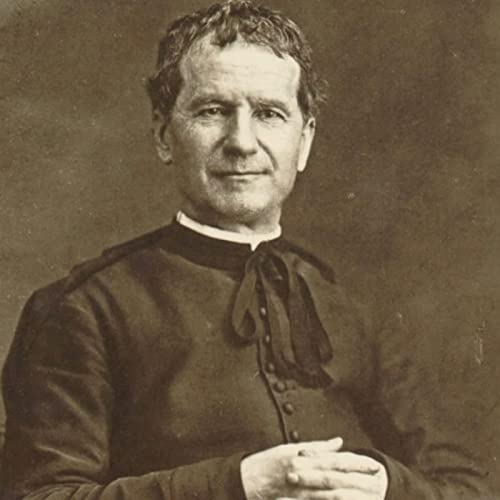

January 31: Saint John Bosco, Priest

1815–1888

Memorial; Liturgical Color: White

Patron Saint of editors, publishers, schoolchildren, and juvenile delinquents

His fatherly heart radiated the warm love of God

Some saints attract the faithful by the raw power of their minds and the sheer force of their arguments. Think of Saint Thomas Aquinas or Saint Augustine. Other saints write so eloquently, with such grace and sweetness, that their words draw people to God like bees to honey. Think of Saint John Henry Newman or Saint Francis de Sales. Still other saints say and write almost nothing, but lead lives of such generous and sacrificial witness that their holiness is obvious. Think of Saint Francis of Assisi or Saint Teresa of Calcutta. Today’s saint was not a first-class thinker, eloquent writer, bloody martyr, or path-breaking Church reformer. Yet his abundant gifts drew people to God in their own unique way.

Saint John Bosco was, to put it in the simplest terms, a winner. His heart was like a furnace radiating immense warmth, fraternal concern, and affectionate love of God. His personality seemed to operate like a powerful magnet that pulled everyone closer and closer in toward his overflowing, priestly, and fatherly love. His country-boy simplicity, street smarts, genuine concern for the poor, and love of God, Mary, and the Church made him irresistible. Don Bosco (‘Don’ being a title of honor for priests, teachers, etc.) had charm. What he asked for, he received. From everyone. He built, during his own lifetime, an international empire of charity and education so massive and so successful that it is impossible to explain his accomplishments in merely human terms.

Like many great saints, Don Bosco’s external, observable charisms were not the whole story. Behind his engaging personality was a will like a rod of iron. He exercised strict self-discipline and firmness of purpose in driving toward his goals. His gift of self, or self-dedication, was remarkable. Morning, noon, and night. Weekday or weekend. Rain or shine. He was always there. Unhurried. Available. Ready to talk. His life was one big generous act from beginning to end.

Saint John grew up dirt poor in the country working as a shepherd. His father died when he was an infant. After studies and priestly ordination, he went to the big city, Turin, and saw first-hand how the urban poor lived. It changed his life. He began a ministry to poor boys which was not particularly innovative. He said Mass, heard confessions, taught the Gospel, went on walks, cooked meals, and taught practical skills like book binding. There was no secret to Don Bosco’s success. But no one else was doing it, and no one else did it so well. Followers flocked to assist him, and he founded the Salesians, a Congregation named after his own hero, Saint Francis de Sales. The Salesian empire of charity and education spread around the globe. By the time of its founder’s death in 1888, the Salesians had 250 houses the world over, caring for 130,000 children. Their work continues today.

Don Bosco was not concerned with the remote causes of poverty. He did not challenge class structures or economic systems. He saw what was in front of him and went “straight to the poor,” as he put it. He did his work from the inside out. It was for others to figure out long-term solutions, not for him. Don Bosco did not know what rest was and wore himself out by being all things to all men. His reputation for holiness endured well beyond his death. A young priest who had met him in Northern Italy in 1883, Father Achille Ratti, later became Pope Pius XI. On Easter Sunday 1934, this same pope canonized the great Don Bosco whom he had known so many years before.

Saint John Bosco, you dedicated your life to the education and care of poor youth. Aid us in reaching out to those who need our assistance today, not tomorrow, and here, not somewhere else. Through your intercession, may we carry out a fraction of the good that you achieved in your life.

Show More

Show Less

Jan 28 20246 mins

Jan 28 20246 mins 6 mins

6 mins Jan 26 20245 mins

Jan 26 20245 mins Jan 25 20245 mins

Jan 25 20245 mins Jan 24 20245 mins

Jan 24 20245 mins Jan 23 20244 mins

Jan 23 20244 mins Jan 22 20245 mins

Jan 22 20245 mins Jan 22 20245 mins

Jan 22 20245 mins